Cryptosystems – Theory

Principles of symmetric block cipher algorithms (Feistel ciphers, DES, AES) and asymmetric algorithms (RSA, Diffie-Hellman, DSA/ElGamal). Factorization and primality testing. Principles of hash function construction. Elliptic curve cryptosystems. (IA174, PV079)

$\def\bin{\{0, 1\}} \def\xor{\oplus} \def\card#1{|#1|} \def\mc{\mathcal}$

Other Sources

Symmetric Block Cipher Algorithms

Symmetric-key algorithms are cryptographic algorithms that use the same keys for both the encryption of plaintext and the decryption of ciphertext. Block ciphers take a fixed number of bits and encrypt them in a single unit, padding the plaintext to achieve a multiple of the block size.

Feistel Ciphers

Block ciphers designed as a Feistel network are called Feistel ciphers.

An $n$-round Feistel network is a composition of $n$ Feistel permutations.

Feistel Permutation

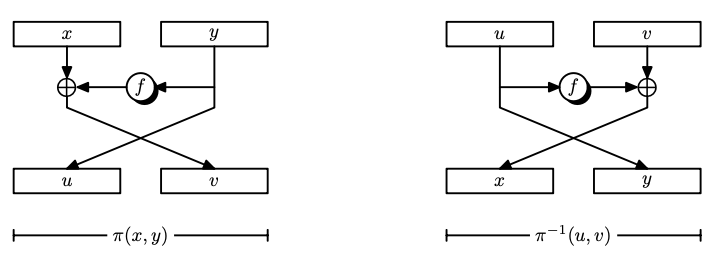

Let $f: \bin^{n} \to \bin^{n}$ be a function. We construct a permutation $\pi: \bin^{2n} \to \bin^{2n}$ as follows:

\[\pi(x, y) := (y, x \xor f(y))\]It is a permutation because the inverse exists:

\[\pi^{-1}(u, v) = (v \xor f(u), u)\] \[\begin{align*} \pi^{-1}(\pi(x, y)) &= \pi^{-1}(y, x \xor f(y)) \\ &= (x \xor f(y) \xor f(y), y) \\ &= (x, y). \end{align*}\]The diagram of the Feistel permutation is below:

DES

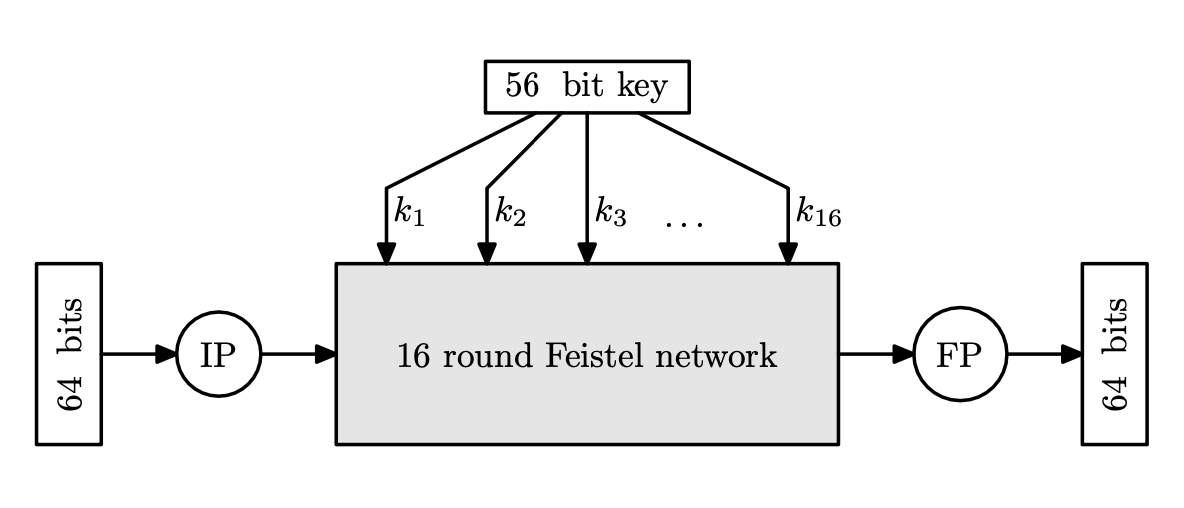

The Data Encryption Standard is a symmetric-key algorithm. It has a key length of 56 bits, making it insecure for modern applications. It operates on blocks of 64 bits.

DES is a Feistel cipher with the Feistel permutation function $f$ taking $32$-bit inputs and the resulting permutation $\pi$ operating on 64-bit blocks.

The DES encryption algorithm is a 16-round Feistel network where each round uses a different $f: \bin^n \to \bin^{2n}$. In the $i$-th round, the function $f$ is defined as

\[f(y) := F(k_i, y),\]where $y$ is the second half of a 64-bit round input, $k_i$ is a 48-bit key for the $i$-th round and $F$ is the DES round function. The first half of the 64-bit round input, $x$, is XORed with $f(y)$, as in the Feistel permutation diagram. The input to the first round is the block to encrypt, the input to the $i+1$-th round is the output of the $i$-th round, the output of the 16th round is the encrypted block.

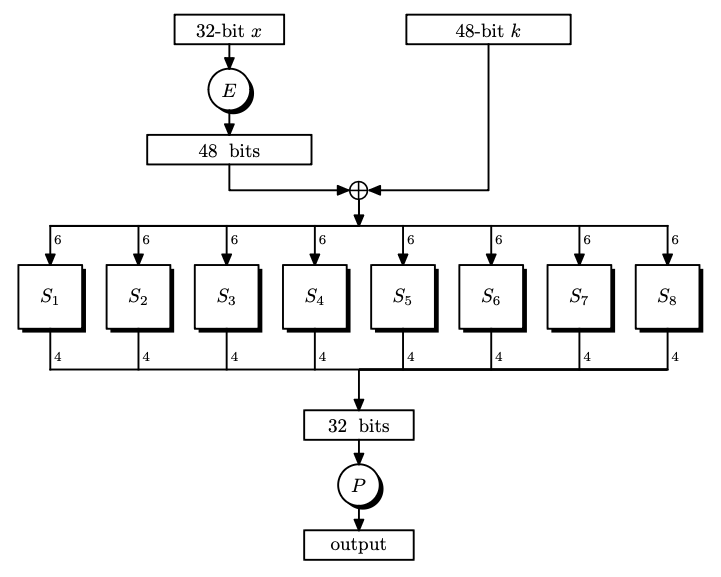

DES Round Function

- The function $E$ expands a 32-bit input to a 48-bit output by rearranging and replicating the input bits.

- The functions $S_1, \dots, S_8$ are called S-boxes. Each S-box $S_i$ maps a 6-bit input to a 4-bit output by a lookup table. The DES standard contains the definitions for these S-boxes.

- The function $P$ (the mixing permutation) maps a 32-bit input to a 32-bit output by rearranging the bits of the input.

The Key Expansion Function

The DES key expansion function $G$ takes as input the 56-bit key $k$ and outputs 16 keys $k_1, \dots, k_{16}$, each 48-bits long. Each $k_i$ is a different subset of 48 bits from $k$.

The DES Algorithm

The complete DES encryption algorithm consists of 16 iterations of the DES round function plus initial and final permutations called IP and FP. The permutation FP is the inverse of IP. IP and FP have no cryptographic significance.

The decryption algorithm is very similar to the encryption one, as the inversion of a Feistel permutation is quite a similar operation to the Feistel permutation itself.

Remarks

In June 1997, the DESCHALL Project breaks a message encrypted with DES for the first time in public. Its small effective key size of 56 bits makes it prone to bruteforce attacks on the key.

The DES cipher has proved to be remarkably resilient to sophisticated attacks. Despite many years of analysis the most practical attack on DES is a brute force exhaustive search over the entire key space.

AES

In 1997, NIST put out a request for proposals for a new block cipher standard to be called the Advanced Encryption Standard. In October 2000, NIST announced that Rijndael, a Belgian block cipher, had been selected as the AES cipher. AES became an official standard in November of 2001 when it was published as a NIST standard in FIPS 197, making it a standard replacement for DES. Rijndael was designed by Belgian cryptographers Joan Daemen and Vincent Rijmen.

AES is an iterated cipher that iterates a simple round cipher several times. The number of iterations depends on the size of the secret key:

| Cipher | Key Bits | Block Bits | Rounds |

|---|---|---|---|

| AES-128 | 128 | 128 | 10 |

| AES-192 | 192 | 128 | 12 |

| AES-256 | 256 | 128 | 14 |

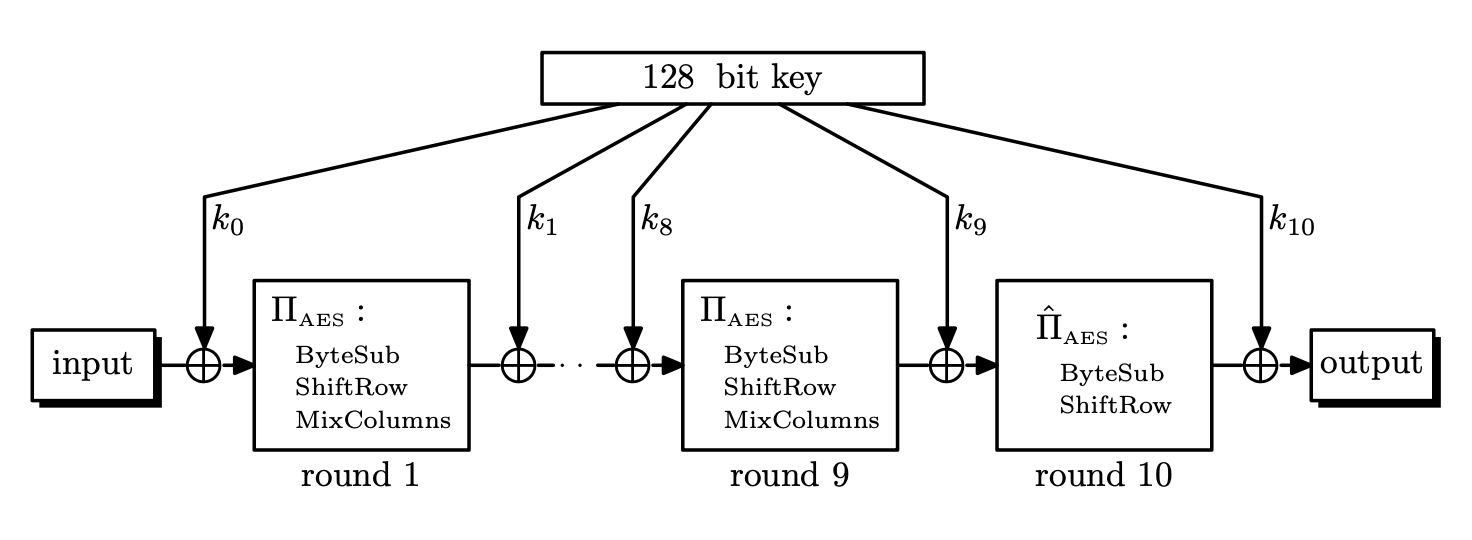

Here \(\Pi_{\text{AES}}\) is a fixed permutation on $\bin^{128}$ that does not depend on the key. The last step of each round is to XOR the current round key with the output of \(\Pi_{\text{AES}}\). This is repeated 9 times, in the last round, MixColumns is omitted. The Rijndael design document, page 7 says

In order to make the cipher and its inverse more similar in structure, the linear mixing layer of the last round is different from the mixing layer in the other rounds. It can be shown that this does not improve or reduce the security of the cipher in any way. This is similar to the absence of the swap operation in the last round of the DES.

Inverting the AES algorithm is done by running the entire structure in the reverse direction. This is possible because every step of the cipher is invertible.

The AES Round Permutation

The permutation \(\Pi_{\text{AES}}\) is a sequence of three invertible operations on $\bin^{128}$, which is represented as an array of $4 \times 4$ cells, each cell having a size of 8 bits.

-

SubBytesThe permutation $S: \bin^8 \to \bin^8$ is applied to every cell individually. The permutation is non-linear, fixed for the whole cipher, and is called the Rijndael S-box. The Rijndael S-box was designed to resist linear and differential cryptanalysis.

The S-box is designed a multiplicative inverse (the special case of $0$ being treated as having an inverse of $0$) of the input in $GF(2^8)$ with the elements being represented as polynomials modulo $p(x) = x^8 + x^4 + x^3 + x + 1$, followed by an affine transformation.

-

ShiftRowsA cyclic shift on the four rows of the input $4 \times 4$ array. The first row is unchanged, the second is shifted one byte to the left, the third row two bytes to the left, and the fourth three bytes to the left:

\[\begin{pmatrix} a_0 & a_1 & a_2 & a_3 \\ a_4 & a_5 & a_6 & a_7 \\ a_8 & a_9 & a_{10} & a_{11} \\ a_{12} & a_{13} & a_{14} & a_{15} \\ \end{pmatrix} \to \begin{pmatrix} a_0 & a_1 & a_2 & a_3 \\ a_5 & a_6 & a_7 & a_4 \\ a_{10} & a_{11} & a_8 & a_9 \\ a_{15} & a_{12} & a_{13} & a_{14} & \\ \end{pmatrix}\] -

MixColumnsA linear operation where the bits of the columns of the array are mixed together. This step is a matrix multiplication in $GF(2^8)$:

\[\begin{pmatrix} [2] & [3] & [1] & [1] \\ [1] & [2] & [3] & [1] \\ [1] & [1] & [2] & [3] \\ [3] & [1] & [1] & [2] \\ \end{pmatrix} \cdot \begin{pmatrix} a_0 & a_1 & a_2 & a_3 \\ a_4 & a_5 & a_6 & a_8 \\ a_8 & a_9 & a_{10} & a_{11} \\ a_{12} & a_{13} & a_{14} & a_{15} & \\ \end{pmatrix},\]where numbers such as $[3]$ represent the elements of $GF(2^8)$ using the binary representation ($[3] = 00000011 = x + 1$).

Every step is invertible, and therefore the whole round permutation is invertible.

Key Expansion

For AES-128, the 128-bit key is used as the first round key $k_0$, unchanged. For the remaining ten round keys, every key is generated from the preceding round key as an invertible operation (because that way all the keys have the same entropy).

Asymmetric Algorithms

One Way Function

A function $f: \bin^* \to \bin^*$ is a one way function (trapdoor function) if it is efficiently computable and for every $n$ and a $poly(n)$ time adversary $A$, the probability over random $x \leftarrow_R \bin^n$ that $A(f(x))$ outputs $x’$ such that $f(x’) = f(x)$ is negligible.

The conjecture that “one way functions exist” is equivalent to the PRF and PRG conjectures.

Public Key Encryption Scheme

A triple of efficient algorithms $(G, E, D)$ is a public key encryption scheme of length function $\ell: \mathbb{N} \to \mathbb{N}$ if:

- $G$ is a probabilistic key generation algorithm that for input $n$ outputs a distribution over pair of keys $(e, d)$ of length $n$

- $E$ is the encryption algorithm that takes a pair of inputs $m, e$ with $m \in \bin^{\ell(n)}$ and outputs $c = E_e(m)$

- $D$ is the decryption algorithm that takes a pair of inputs $c, d$ and outputs $m’ = D_d(c)$

CPA Security for Public-key Encryption

An encryption scheme $(G, E, D)$ is CPA secure if every efficient adversary $A$ wins the following security game with probability at most $\frac{1}{2} + negl(n)$:

- $(e, d) \leftarrow_R G(n)$

- $A$ is given $e$ and outputs a pair of messages $m_0, m_1 \in \bin^{n}$

- $A$ is given $c = E_e(m_b)$ for $b \leftarrow_R \bin$

- $A$ outputs $b’ \in \bin$ and wins if $b’ = b$

RSA (Vanilla)

RSA uses the fact that prime factoring is regarded as a computationally hard problem, however multiplying two large primes is computationally easy. RSA is only a trapdoor function given our current state of knowledge.

Key Generation

- Two prime numbers $p, q$ of roughly the same bitlength and satisfying additional security conditions are randomly generated. We compute $n = p \cdot q$

- We select a public exponent $e$ co-prime to $\varphi(N) = (p - 1) \cdot (q - 1)$ and compute its multiplicative inversion $d$ in $\mathbb{Z}_{\varphi(N)}^\times$, i.e. $e \cdot d \equiv 1 \pmod{(p - 1) \cdot (q - 1)}$

- We output the public key $k_p = (N, e)$ and the private key $k_s = (N, d)$.

Encryption

$E_{k_p}(m) = m^e \pmod{N}$

Decryption

$D_{k_s}(c) = c^d \pmod{N}$

Vanilla RSA should never be used directly for encryption as it is insecure. As it is a deterministic scheme, it is not CPA secure.

Diffie-Hellman Key Exchange

Diffie-Hellman Key Exchange is an algorithm for the computation of a shared secret between two parties. Its security is built on the presumed difficulty of the discrete logarithm problem in cyclic groups.

Discrete Logarithm

Let $(G, .)$ be a finite cyclic group, $b \in G$ a generator of the group, and $k \in {0, \dots, ord(b) - 1}$. For $y = b^k$, the value $k$ is called the discrete logarithm of $y$ with reference to base $b$ in $G$, written $k = dlog^G_b(y)$. For a proper choice of $G$ and $b$ the discrete logarithm is believed to be difficult to compute given the knowledge of $G, \card{G}, b$, and $y = b^k$.

The proper choice criteria include:

- $\card{G}$ should be sufficiently large to prevent DL computation by bruteforcing, or the baby-step giant-step algorithm

- the $.$ operation of $G$ should be efficiently computable

- $\card{G}$ should not be smooth to prevent against attacks exponential in the bitsize of the largest prime factor of $\card{G}$

- Pohlig-Hellman, Pollard’s $\rho$

The typical choices for $G$ are $\mathbb{Z}_p^\times$ for a large prime $p$ such that $p - 1$ is not smooth, or groups generated by elliptic curves.

Diffie-Hellman

Setup

Alice and Bob agree in advance on a cyclic group $G$ of order $\card{G}$ and on its generator $b$. They also fix a method for translating the elements of $G$ into symmetric keys. The setup phase can be negotiated over an insecure channel.

Exchange

- Alice randomly samples a number $\alpha \in {1, \dots, \card{G} - 1}$ and sends $m_A = b^\alpha$ to Bob.

- Bob randomly samples a number $\beta \in {1, \dots, \card{G} - 1}$ and sends $m_B = b^\beta$ to Alice.

Key Derivation

Alice computes $m_B^\alpha = m^{\beta\alpha} = k$. Bob computes $m_A^\beta = m^{\alpha\beta} = k$.

Diffie-Hellman key exchange is considered to be secure against passive adversaries. However, it lacks authentication mechanisms and therefore it is susceptible to active man-in-the-middle attacks.

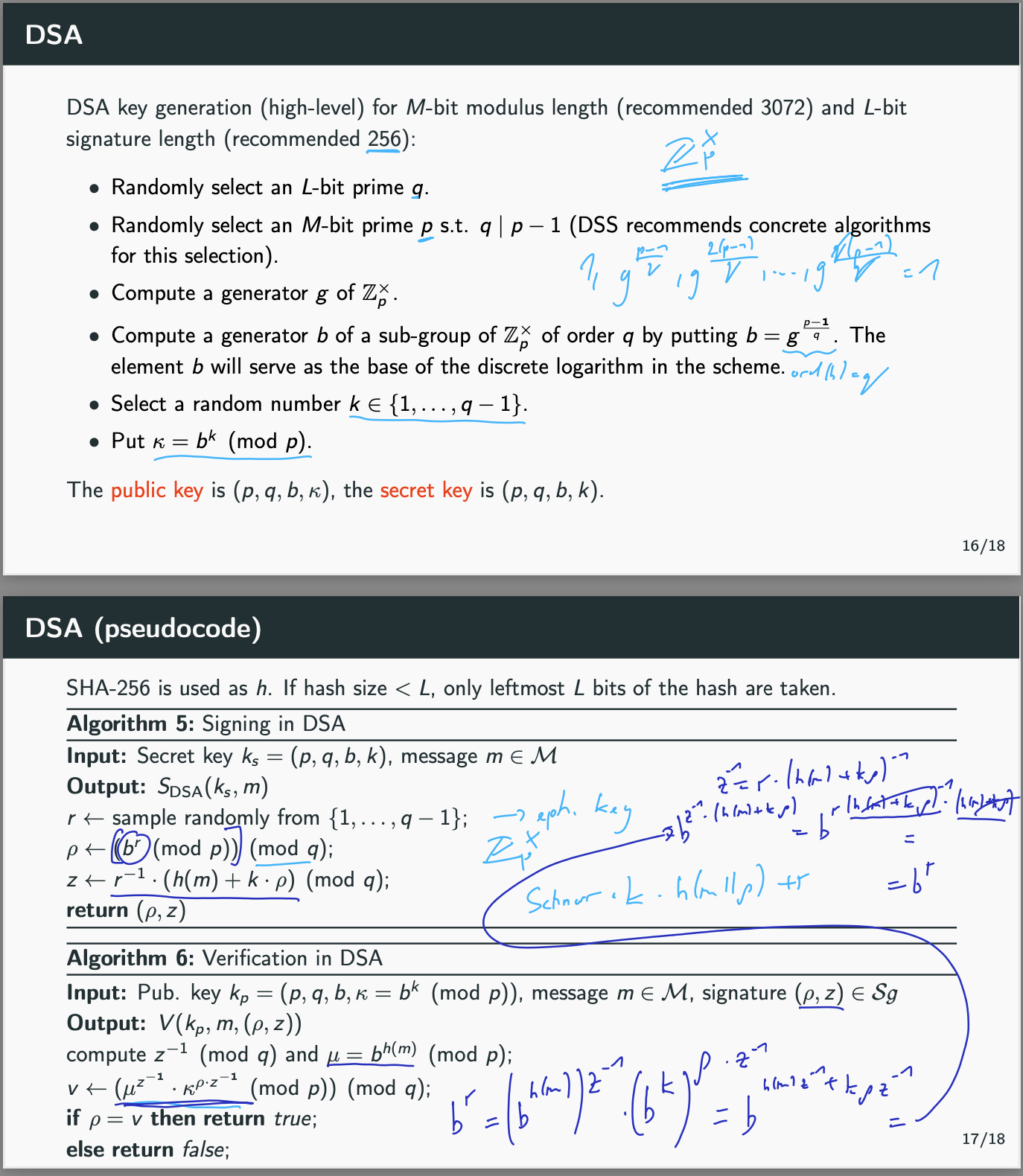

DSA

Digital signature algorithm is a digital signature scheme based on the discrete logarithm problem in $\mathbb{Z}_p^\times$.

ElGamal (Encryption)

Bob chooses a large prime $p$, a generator $q \leq p$, an integer $x$, computes $y = q^x \pmod{p}$, makes $(p, q, y)$ public and keeps $x$ secret. To send a message $m$, Alice chooses a random $r$, computes

\[\begin{align*} a &\equiv q^r &\pmod{p}\\ b &\equiv m \cdot y^r &\pmod{p}\\ \end{align*}\]Ciphertext: $c = (a, b)$

To decrypt, Bob takes $c$ and calculates

$b \cdot a^{-x} \equiv m \cdot y^r \cdot q^{-xr} \equiv m \cdot q^{xr} \cdot q^{-xr} \equiv m \pmod{p}$.

Integer Factorization and Primality Testing

Euclid theorem states that we can uniquely factor every integer $n$ into a power of primes

\[n = \prod_{i=1}^k{p_i^{e_i}}\]However, finding the prime factors is not computationally trivial.

- Integer Factorization: If $n$ can be factorized, find its factors.

- assumed to be hard problem (one of the few hard problems used for cryptography)

- best asymptotic running time for found algorithms is sub-exponential (GNFS)

- factorization can be done in polynomial time on a quantum computer using Shor’s algorithm

- Primality testing: Can a given integer $n$ be factorized?

- polynomial deterministic algorithm exists (AKS primality test), although not used in practice

- in practice (OpenSSL), prime testing is done by trial division by a number of small primes and rounds of the of the Rabin-Miller probabilistic primality test (at least 64 rounds, giving a maximum false positive rate of $2^{-128}$)

Integer Factorization Algorithms

Trial Division

Divide $n$ with all primes $2, 3, 5, \dots$ up to $\sqrt{n}$ or until you find a factor. If the factor is not found, $n$ is prime. Each time you divide $n$ by a prime, delete all multiples of the prime from the list of considered integers (sieve of Eratosthenes).

Time complexity: $e^{\frac{1}{2}\ln{n}}$ (exponential)

Pollard’s Rho Factorization

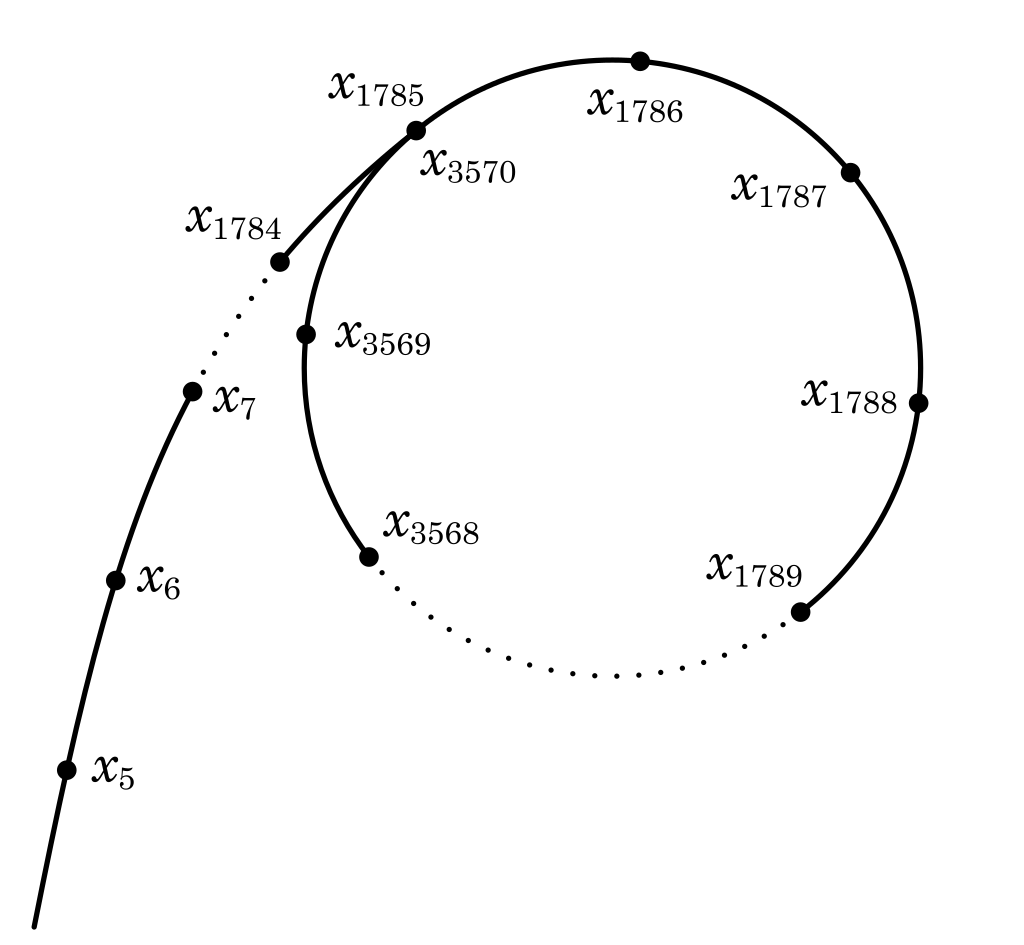

The algorithm is used to factor $n = pq$, with the method working good for one of $p, q$ being quite small.

We choose $x_0$ and a polynomial $f(x)$ (typically $x_0 = 2, f(x) = x^2 + 1$). Then we set $x = x_0, y = y_0$ and use Floyd’s cycle-finding algorithm (tortoise and hare) to compute repeatedly:

\[\begin{align*} x &\equiv f(x) &\pmod{n}\\ y &\equiv f(f(y))&\pmod{n}\\ d &= \gcd(|x - y|, n) & \end{align*}\]If $d$ is not equal to $1$, we found a cycle in the sequence and therefore we found either $x \equiv y \pmod{n}$ or $x \equiv y \pmod{p}$ for one of the non-trivial factors $p$. The latter is more probable as due to the birthday paradox the expected length of the cycle in ${x_k} \pmod{p} = \sqrt{p} < < \sqrt{n}$.

So if $d \not= 1$, we terminate the algorithm. Now $d$ is either a non-trivial factor of $n$ (which we were searching for), or it is $n$. In that case we may repeat the algorithm with different choices of $x_0$ and $f(x)$.

Complexity: proportional to the square root of the size of the smallest prime factor (this is not rigorous)

Primality Testing

Fermat Test

Input: $n > 3$ - integer to test for primality, $k$ - number of times to check for primality

Repeat $k$ times:

- Pick $a$ in range $[2, n - 2]$.

- If $a^n \not\equiv a \pmod{n}$, $n$ is composite, halt.

If the algorithm is not halted after $k$ times, we say that $n$ may be prime. However, Carmichael numbers are composite numbers where for all $a$ such that $\gcd(a, n)$ it holds that $a^n \equiv a \pmod{n}$, therefore Fermat test for the Carmichael numbers is computationally equivalent to bruteforce searching for the factors.

Rabin-Miller Algorithm

Rabin-Miller is an extension of the Fermat test that uses the extra information that the only roots of $x^2 - 1 \pmod{p}$ (this is equivalent to $x^2 \equiv 1 \pmod{p}$) are $x = \pm{1}$ iff $p$ is prime, because for

\[(x + 1)(x - 1) \equiv 0 \pmod{p}\]the only solutions for $x$ are $\pm{1}$ if $p$ is prime. For composite moduli $n = p_1 \dots p_k$ we can use the CRT to compute solutions to $x^2 - 1$ over each $\mathbb{Z}_{p_i}$ and combine the roots together to find the solutions modulo $n$. Therefore there are $2^k$ different roots of the polynomial for composite $n$.

We start with checking whether $a^{n - 1} \equiv 1 \pmod{n}$ (this is exactly Fermat test), but if it passes, we continue with checking $a^{(n - 1)/2} \equiv \pm 1 \pmod{n}$, as $a^{(n - 1) / 2}$ is a square root of $1$. We continue halving the exponent until we reach a number besides $1$. If it’s not equal to $-1$, then $n$ must be composite (as the theorem above does not hold).

For any composite $n$ (including Carmichael numbers), the probability it passes a single instance of the Rabin-Miller test is at most $\frac{1}{4}$. Therefore, with $k$ rounds of Rabin-Miller we know that $n$ is prime with probability at least $2^{-2k}$.

Principles of Hash Function Construction

A hash function maps long strings from a set $M = \bin^{\leq L}$ onto short strings (called hashes) from a set $H = \bin^{\ell}$, where $\ell < < L$.

Cryptographic hash functions require one-way and collision resistance properties: given a hash of a message, it is difficult to compute the message, or to compute two messages that hash to the same string.

- Unkeyed hash functions $h: M \to H$

- message/file integrity

- password storage

- digital signatures

- Keyed hash function (MAC): $h: M \times K \to H$

- message integrity and authenticity

We will continue talking only about unkeyed hash functions in this section.

Desired Properties

- $h$ is one-way (first-preimage resistant)

- given $h(m)$, it is difficult to compute $m$

- $h$ is second-preimage resistant

- given $m$ and $h(m)$, it is difficult to compute $m’ \not= m$ such that $h(m’) = h(m)$

- $h$ is collision resistant

- it is difficult to compute $m, m’$ such that $m’ \not= m$ and $h(m’) = h(m)$

Existence of one-way functions would imply $P \not= NP$. None of the practically used hash functions was broken w.r.t. one-wayness. Older hash functions such as MD5 and SHA-1 were broken w.r.t. collision resistance - no longer deemed secure.

Additional Properties

- non-correlation (avalanche effect): small change of $m$ should elicit large and random-looking change of $h(m)$

- local preimage resistance: given $h(m)$ it should be difficult to obtain e.g. short substrings of $m$

Hash Function Construction

Merkle-Damgård Construction

Basic idea: extend functions that hash short messages into functions that hash messages of arbitrary length.

Compression function for a hash space $H = \bin^\ell$ is a function $f: \bin^\ell \times \bin^k \to \bin^\ell$ for $k \approx \ell$.

An MD hash function $h: \bin^{\leq L} \to \bin^\ell$ is specified by the following parameters:

- a compression function $f: \bin^\ell \times \bin^k \to \bin^\ell$,

- an MD-compliant padding scheme $\text{pad}: \bin^{\leq L} \to \bin^{\times k}$, where $\bin^{\times k}$ is the set of all bit strings whose length is a multiple of $k$.

The construction first pads the message $m$ using $\text{pad}$ so that its length is a multiple of $k$. Then, the following diagram shows the calculation of the hash:

The initial state $s$ is a constant specified in the definition of the MD hash function $h$.

MD-compliant Padding

A padding scheme $\text{pad}: \bin^{\leq L} \to \bin^{\times k}$ is MD-compliant if it satisfies the following three properties for all $m, m’ \in M$:

- $m \not= m’ \implies \text{pad}(m) \not= \text{pad}(m’)$

- $\text{len}(m) = \text{len}(m’) \implies \text{len}(\text{pad}(m)) = \text{len}(\text{pad}(m’))$

- $\text{len}(m) \not= \text{len}(m’) \implies$ the last $k$-bit block of $\text{pad(m)}$ differs from the last $k$-bit block of $\text{pad}(m’)$

A padding that is MD-compliant is for example the Merkle padding:

\[\text{pad}(m) = m || 1 || 0^d || \text{len}(M)\]where $d$ is the smallest positive integer that makes the output’s length a multiple of $k$, and $\text{len}(M)$ being represented by a bitvector of a fixed size (typically 64 or 128 bits).

Davies-Meyer Compression Function

$f(s, b) = E(b, s) \xor s$, where $s$ is the input state, $b$ a block of message to be hashed and $E$ a block cipher.

Practical hash functions do not use “mainstream” block ciphers such an AES. AES and similar algorithms are optimized for the scenario when the same key is used to encode many blocks in a row. But in the MD construction, performance when changing keys rapidly is key. Hash functions use tailor-made “block ciphers” as compression functions.

- major obsolete MD-based hash functions: MD5, SHA-1

- state-of-the-art MD-based hash function: SHA-2

All of these use the Davies-Meyer compression function with a custom block cipher (for example SHACAL-2 in the case of SHA-2).

Hash functions using the Merkle-Damgård Construction are vulnerable to length extension attacks.

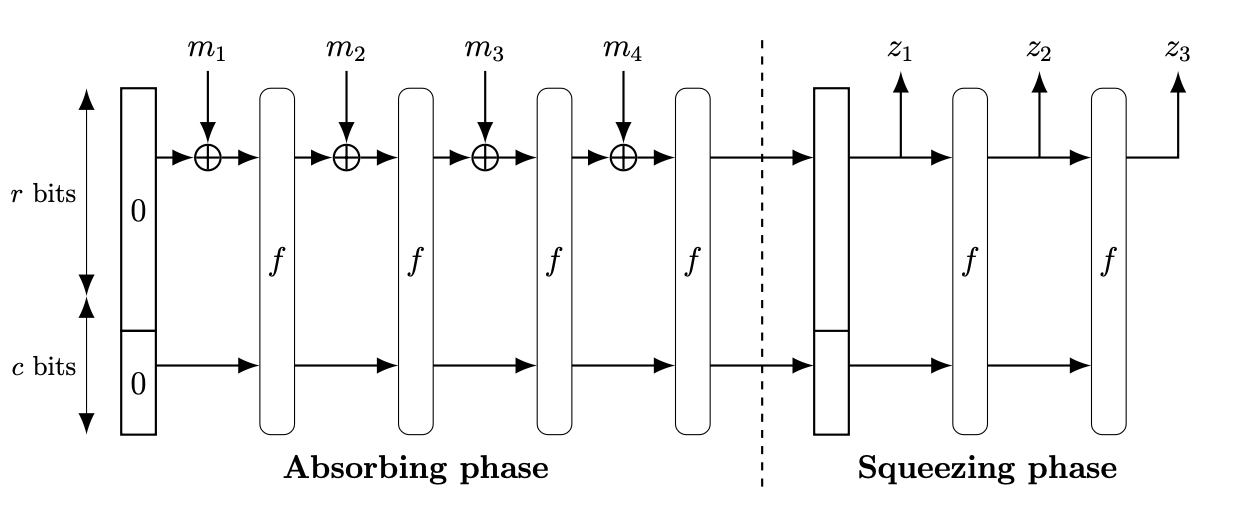

Sponge Construction

Sponge construction is a generic construction mapping arbitrary-length input bitstreams to arbitrary length output bitstreams, which gives the algorithms a large variability of use (hash functions, PRGs, …).

A sponge construction is determined by

- state bitlength $n$, capacity $c$ and rate $r$; $n = c + r$

- padding function $\text{pad}$ that pads to a length that is multiple of $r$ (any injective function)

- round permutation $\pi: \bin^n \to \bin^n$, which should be indistinguishable from a random permutation

To hash a long message $m \in \bin^{\leq L}$, we append the padding to make its length a multiple of $r$, and then break $m$ into sequence of $r$-bit block $m_1, \dots, m_s$. In the absorbing phase, in every block, $m_i$ gets mixed (XORed) with the first $r$ bits of the hidden state, and the remaining $c$ bits cannot be tampered with. Then, the whole hidden state is run through the round permutation and serves as an input to the next round. The capacity $c$ must be large for the sponge construction to be secure (collision resistant).

The output length in the SHA3 standard is fixed to $v \leq r$, so the squeezing stage in that case is just outputting the first $v$ bits of $h$.

Keccak (SHA-3)

- family of functions, uses $r + c = 1600$ with variable capacities

- a complex permutation $\pi: \bin^{1600} \to \bin^{1600}$ consisting of variable number of rounds

- padding appends $1 0^* 1$

Elliptic Curve Cryptosystems

EC Introduction

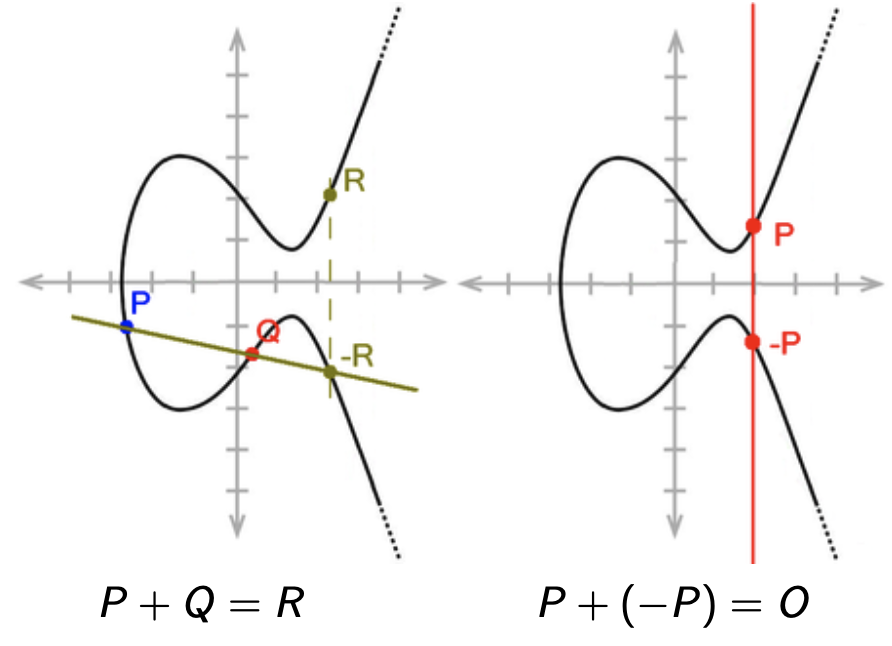

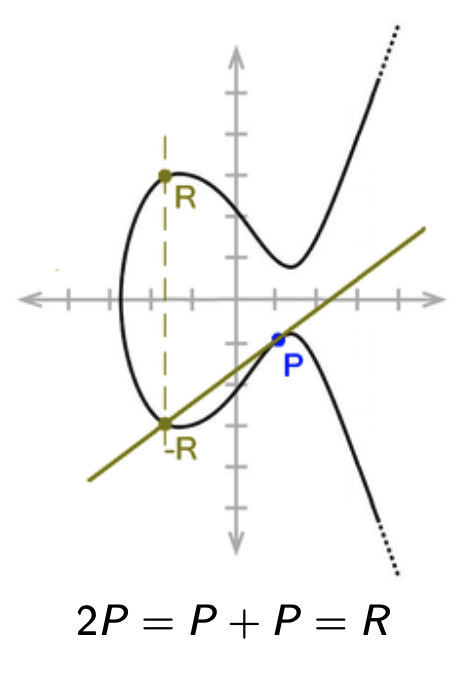

Let $F$ be a field of a characteristic different than 2 or 3 and $a, b \in F$ such that $4a^3 + 27b^2 \not = 0$ (we do not want to use singular curves). An elliptic curve over $F$ is the set of points $(x, y) \in F^2$ satisfying the Weierstrass equation

\[y^2 = x^3 + ax + b\]together with the special point at infinity $\mc{O}$. In cryptography, we usually use $F = \mathbb{F}_p$ with prime $p \geq 5$.

Each elliptic curve $E$ defines a group $(E, +)$ where the group operation $+$ has the following geometric meaning:

If $x_1 = x_2$ and either $y_1 \not= y_2$ or $y_1 = y_2 = 0$, then $(x_1, y_1) + (x_2, y_2) = \mc{O}$. $\mc{O}$ is the neutral element of the group, i.e. $P + \mc{O} = \mc{O} + P = P$ for every $P \in E$.

The EC group is always cyclic or bicyclic.

ECDH

The same as the Diffie-Hellman algorithm explained above, but we use an elliptic curve modulo a large prime field $\mathbb{F}_p$ as the group.

ECDSA

ECDSA is based on DSA but the group is again an elliptic curve modulo a large prime field $\mathbb{F}_p$.

Discrete Logarithm

We use additive notation with EC groups. A $k$-fold application of the group operation $+$ is denoted as

\[k \cdot P = P + \dots + P\]where the addition is done $k$ times.

The discrete logarithm problem over elliptic groups is: Given a group $(E, +)$ defined by an elliptic curve, a point $G$ on the curve, and a point $P = k \cdot G$, find $k$.