Entropy, Random Generation, Cryptographic Protocols

$\def\F{\mathbb{F}} \def\R{\mathbb{R}} \def\E{\mathbb{E}} \def\N{\mathbb{N}} \def\Z{\mathbb{Z}} \def\C{\mathbb{C}} \def\mc{\mathcal} \def\Im{\text{Im}} \def\Var{\text{Var}} \def\MSE{\text{MSE}} \def\abs#1{|#1|} \def\bigabs#1{\left|#1\right|} \def\st{~|~} \def\set#1{\{#1\}} \def\condset#1#2{\{#1~|~#2\}} \def\bf{\mathbf} \def\bb{\mathbb}$

Basics of coding theory, Shannon’s theorem. Entropy. Generation of truly- and pseudo-random sequences. Cryptographic protocols, methods of key establishment, zero-knowledge protocols. Quantum cryptography. (IV054, PV079)

Other Sources

- https://hackmd.io/@rsss-statnice2022/Bk1FK4qO5

- http://statnice.dqd.cz/mgr-szz:in-bit:1-bit

- http://statnice.dqd.cz/mgr-szz:in-bit:5-bit

Coding Theory

A code $C$ over an alphabet $\Sigma$ is a nonempty subset of $\Sigma^{*}$. A $q$-ary code is a code over an alphabet of $q$ symbols. A binary code is a code over the alphabet $\set{0, 1}$.

A discrete Shannon stochastic channel is described by a triple $C = (\Sigma, \Omega, P)$, where

- $\Sigma$ is an input alphabet,

- $\Omega$ is an output alphabet,

- $P: \Sigma \times \Omega \to \set{0, 1}$ is the probability that the output of the channel is $o$ if the input is $i$.

Hamming Distance

Hamming distance of words $x, y$ is the number of symbols in which the words $x$ and $y$ differ.

An important parameter of codes is their minimal distance, which is the smallest number of errors that can change one codeword into another.

\[h(C) = \min\condset{h(x, y)}{x, y \in C, x \not= y}\]Error Correcting Theorems

- A code $C$ can detect up to $s$ errors if $h(C) \geq s + 1$.

- A code $C$ can correct up to $t$ errors if $h(C) \geq 2t + 1$.

An $(n, M, d)$ code $C$ is a code such that

- $n$ is the length of codewords,

- $M$ is the number of codewords,

- $d$ is the minimum distance of two codewords in $C$.

We strive to design codes with small $n$, large $M$ and large $d$.

Linear Codes

We fix our alphabet to be elements of $\F_q$, where $q$ is (a power of) a prime. $\F_q^n$ is the vector space of all $n$-tuples over $GF(q)$.

$C \subseteq \F_q^n$ is a linear code if

- $u + v \in C$ for all $u, v \in C$,

- $au \in C$ for all $u \in C, a \in GF(q)$.

A subset $C \subseteq \F_q^n$ is a linear code iff one of the following conditions is satisfied:

- $C$ is a linear subspace of $\F_q^n$.

- Sum of any two codewords from $C$ is in $C$ (for the case $q = 2$).

(nothing surprising here, linear codes are simple vector spaces)

If $C$ is a $k$-dimensional subspace of $\F_q^n$, then $C$ is called $[n, k]$-code. It has $q^k$ codewords. If the minimal distance of $C$ is $d$, then it is said to be the $[n, k, d]$ code.

A base $B$ of $C$ is a set of $k$ codewords of $C$ such that each codeword of $C$ is a linear combination of the codewords from the base $B$ (the span of $B$ is $C$). The base can be represented by a $(k, n)$ matrix $G_B$: the generator matrix of $C$, the $i$-th row of which is the $i$-th codeword of $B$.

Let $w(x)$ (weight of $x$) denote the number of non-zero entries of $x$.

Let $C$ be a linear code and let the weight of $C$ ($w(C)$) be the smallest of the weights of non-zero codewords of $C$. Then $h(C) = w(C)$.

Equivalent Linear Codes

Two $k \times n$ matrices generate equivalent linear $[n, k]$-codes over $\F_q^n$ if one matrix can be obtained from the other by a sequence of the following operations:

- permutation of the rows,

- multiplication of a row by a non-zero scalar,

- addition of one row to another,

- permutation of columns,

- multiplication of a column by a non-zero scalar.

Operations 1.-3. replace one basis by another. Operations 4. and 5. convert a generator matrix to one of an equivalent code.

By operations 1.-5., every generator matrix $G^\prime$ can be transformed into the standard form:

\[G = [I_k | A]\]where $I_k$ is the $k \times k$ identity matrix and $A$ is a $k \times (n - k)$ matrix.

Encoding/Decoding

The generator matrix $G$ of a $[n, k]$-code over $\F_q^n$ generates the codewords $w \in \F_q^n$ of a linear code $C$ by

\[w = sG\]where $s \in \F_q^k$ is any input keyword.

Given a linear $[n, k]$-code $C$, the dual code of $C$, denoted by $C^\perp$, is defined by

\[C^\perp = \condset{v \in \F_q^n}{v \cdot u = 0 \text{ for all } u \in C}\]where $\cdot$ is the inner (scalar) product of two vectors.

We decode $C$ by creating the parity check matrix $H$, which is the generator matrix of the dual code $C^\perp$. If $G$ is the generator matrix of $C$ in standard form, then $H$ is the $(n - k) \times n$ matrix defined as

\[H = [-A | I_{n - k}]\]Decoding random linear codes is an NP-complete problem! However, there exist classes of codes which are easy to both encode and decode, such as the Hamming codes.

Given the parity-check matrix $H$, then we decode by computing the syndrome:

- $S(y) = yH^T$

- If $S(y) = 0$, then $y$ is the codeword sent.

- If $S(y) \not = 0$, then assuming a single error, the $i$-th row of $H^T$ is the same as $S(y)$ and represents that the error happened at the $i$-th position.

Hamming Code

Let $r$ be an integer and $H$ be an $r \times (2^r - 1)$ matrix which has non-zero distinct words from $\F_2^r$ as columns. The code having $H$ as its parity-check matrix is called binary Hamming code and denoted by Hamming($2^r - 1$, $2^r - 1 - r$).

Hamming codes are perfect codes - they they achieve the highest possible rate for codes with their block length and minimum distance of three. Hamming codes detect one-bit and two-bit errors, or correct one-bit errors without detection of uncorrected errors.

Other Codes

Reed-Solomon codes are $[n, k, n - k + 1]$ linear codes. They are widely used (in QR codes for example). It’s based on creating redundant information by evaluating a polynomial at more values of $x$ than is strictly necessary.

Polar codes and Turbo codes are other widely used families (3G, 4G, 5G networks) of linear block codes. The channel performance of these codes almost close the gap to the Shannon limit.

Entropy

Also check out Probability, Theory of Information for equivalent definitions with IV111 notation. These ones follow the IV054 slides.

Let $X$ be a random variable which takes a value $x$ with probability $p(x)$. The entropy of $X$ is defined by

\[S(X) = -\sum_{x \in \Im(X)}{p(x) \log p(x)}\]Shannon’s Noiseless Coding Theorem

Shannon’s noiseless coding theorem says that in order to transmit $n$ values of $X$, we need, and it is sufficient, to use $nS(X)$ bits.

Generation of Random Sequences

- quality and unpredictability is important for random data in cryptography (keys, padding, nonces, …)

The problem: difficulty to obtain a sufficient truly random data The solution: pseudorandom generators

Generating Truly Random Numbers

- based on nondeterministic physical phenomena (radioactive decay, thermal noise, etc.)

- hard and slow to do in deterministic environments

- quality strongly dependent on source of randomness

- excellent: hardware-based

- good: inputs (exact timing of keystrokes, exact movement of mouse, microphone, webcam)

- acceptable (in some cases): software-based (process, network, I/O completion statistics)

- bad (insufficient entropy): predictable, system date/time, process ID

Generating Pseudorandom Numbers

- pseudo- or deterministic random number generation (PRNG/DRNG)

- generated by deterministic algorithm

- short input (seed) - truly random data

- output - pseudorandom data, computationally indistinguishable from truly random data

- quality assurance of particular generators

- cryptanalytical methods, statistical testing

PRNG is a deterministic finite state machine, it has an internal state:

- the state is secret (generator outputs must be unpredictable for cryptographic purposes)

- the state is repeatedly updated (generator must produce different outputs)

Basic types of PRNG utilize:

- LFSR, hard problems of number and complexity theory, typical cryptographic functions/primitives

- entropy pooling in the last case - Yarrow, Fortuna (used as Apple’s kernel CPRNG)

Linear Feedback Shift Register

- input bit is a linear function of its previous state

- typically XOR of some bits from its state

- output is a pseudorandom bit

- repeating cycles: finite number of possible states

- linearity of output: subject of cryptanalysis

- not suitable for cryptographic purposes

- non-linear combination of several LFSR could be used

- using one LFSR to clock another LFSR (alternating step generator, shrinking generator)

Cryptographically Secure RSA & BBS PRNGs

- RSA PRNG based on public-key RSA

- $n = pq, \gcd(e, \varphi(n)) = 1$

- for $i$ from $1$ to $m$ do:

- $x_i = (x_{i-1})^e \pmod{n}$

- $z_i = \text{lsb}(x_i)$ (take the least significant bit of $x_i$ as the output)

- Blum Blum Shub PRNG similar

- uses $x_i = (x_{i-1})^2 \pmod{n}$ instead

- BBS is unusable in practice - it is very slow

- and the proof of security is weak for parameters used in practice (modulus size vs. bits extracted)

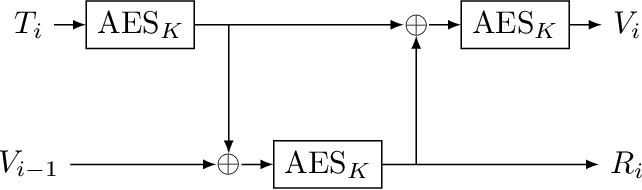

ANSI X9.17/X9.31

- based on 64-bit 3DES or 128-bit AES

- the key $K$ reserved for the generator

- seed is a 64/128-bit value $V$

- $T$ is a 64/128-bit representation of the date/time

- updated on each iteration

- randomly initialized counter can also be used

- in each iteration:

- $I_i = E_K(T_i)$

- $R_i = E_K(I_i \oplus V_{i-1})$ (this is the output)

- $V_i = E_K(I_i \oplus R_i)$

- should not be used, ANSI X9.31 was removed from the list of FIPS-approved random number generation algorithms in January 2016

- vulnerable to the DUHK Attack - if the secret key of the block cipher is known, then all previous and future outputs of the generator can be recovered from 16 bytes of output and a guess for the timestamp

- NIST SP 800-90A Rev. 1 approves three different DRBG methods: Hash_DRBG (using a hash function), HMAC_DRBG (using an HMAC), CTR_DRBG (using a block cipher in counter mode).

Cryptanalytic Attacks

- Direct cryptanalytic attacks

- attacker is able to distinguish between PRNG outputs and random outputs

- usually based on cryptanalysis of underlying primitive

- Input-based attacks

- attacker is able to use the PRNG input(s) to distinguish betweeen PRNG output and random values

- attack fails when user input is hashed before sending to PRNG

- State compromise attacks

- attacker misuses previously compromised state to distinguish PRNG outputs from random values

- PRNGs described above will never recover from a state compromise

- a good design of PRNG expects that state compromise may occur

- mixing data with small amounts of entropy to secret state

State Compromise Resistant PRNGs

- entropy accumulator - collects entropy samples in two pools

- fast and slow pool maintained on the fly

- reseed mechanism - periodically reseeds the key from the pools

- fast pool for frequent reseeds, slow pool for rare reseeds

- reseed control - determines when a reseed is to be performed

- based on entropy estimators

- Yarrow-160 uses 3DES, SHA-1

- Fortuna uses one of AES/Serpent/Twofish as the block cipher and SHA-256

- deals with entropy in a better way

- 32 pools for collecting entropy

- pool $P_i$ is used every $2^i$-th reseed

- deals with entropy in a better way

Statistical Testing of Randomness

- we use statistical tests on the generated random sequences

- particular tests based on test statistic

- standard test batteries: Diehard, Dieharder, TestU01, BoolTest (made by CRoCS)

- NIST battery uses test statistics and P-values

- statistic of bits (number of 1s, longest 1 sequence, etc.)

- statistics of $m$-bit blocks - their frequency

- complex statistic of $m$-bit parts - linear complexity, matrix rank

- generators that pass such tests are considered “good”

- NIST battery uses test statistics and P-values

Cryptographic Protocols

A protocol is a multi-party algorithm defined by a sequence of steps precisely specifying the actions required of two or more parties in order to achieve a specified objectives.

Objectives of cryptographic protocols:

- confidentiality (secrecy)

- authentication of origin

- entity authentication

- integrity

- key establishment

- non-repudiation

- …

Authentication

Shared-key crypto:

- based on trust in the party the key is shared with

- authentication ~ ability to encrypt/decrypt (or MAC)

Public-key crypto:

- based on trust in the party possessing the private key and

- trust in link between the public key and other data

- authentication ~ ability to sign or decrypt messages

Methods of Key Establishment

Key establishment protocols establish a shared secret to two or more parties for subsequent cryptographic use.

- Key Transport: one party securely transfers a secret value to other(s)

- Key agreement: shared secret is derived by two (or more) parties based on data contributed by, or associated with, each of these, and that no party can predetermine the resulting value

Zero-knowledge Protocols

A zero-knowledge proof is a method of proving the validity of a statement without revealing anything other than the validity of the statement itself.

A zero-knowledge proof of some statement must satisfy three properties:

- Completeness: If the statement is true, an honest verifier (verifier who follows the protocol) will be convinced of the fact by an honest prover.

- Soundness: If the statement is false, no cheating prover can convince an honest verifier that it is true, except with a marginal probability.

- Zero-knowledge: If the statement is true, no verifier learns anything other than the fact that the statement is true. This is formalized by the property of the transcripts of the runs of the protocol being easily produced (anyone can create interactions which look like valid runs of the protocol, without the knowledge of any further information - an efficient simulator exists).

An interactive zero-knowledge proof is made up of three elements:

- Witness: The secret information that the prover has and does not want to disclose. The prover’s assumed knowledge of the witness establishes a set of questions that can only be answered by a party with knowledge of the information.

- Challenge: The verifier randomly picks a question from the set and asks the prover to answer it.

- Response: The prover accepts the question, calculates the answer, and returns it to the verifier. To ensure the prover is not guessing blindly, the verifier picks more questions to ask. By repeating this interaction, the possibility of the prover faking knowledge of the witness drops significantly (but is never 0) until the verifier is satisfied.

Example zero-knowledge proofs:

- proving knowledge of non-isomorphism of two graphs, or other hard problems (discrete logarithms, factoring of a large prime)

- Ali Baba cave

Non-interactive zero-knowledge proofs (zk-SNARK) are used in Zcash, a cryptocurrency.

Quantum Cryptography

In classical computers, information is represented on macroscopic level by bits, which can take one of the two values 0 or 1. In quantum computers, information is represented on microscopic level using qubits, which can take on any from the from the uncountable many values

\[\alpha\ket{0} + \beta\ket{1}\]where $\alpha, \beta \in \C$ such that

\[\abs{\alpha}^2 + \abs{\beta}^2 = 1\]An $n$ bit classical register can store one $n$-bit string. An $n$-qubit quantum register can store a superposition of all $2^n$ $n$-bit strings. On a quantum computer, one can “compute” in a single step all $2^n$ values of a function defined on $n$-bit inputs.

Grover’s Algorithm

We are given a function $f: \set{0, 1, \dots, N - 1} \to \set{0, 1}$ such that there exists only one $x$ for which $f(x) = 1$.

Task: find $x$.

Best classical solution: bruteforce ($\mc{O}(N)$ calls to $f$) Assuming that $f$ can be evaluated by a quantum computer, we can use Grover’s algorithm to find $x$ in $\mc{O}(\sqrt{N})$ calls to $f$.

Grover’s algorithm speeds up bruteforce attacks against symmetric cryptography, but doubling the key size is enough to ensure the same amount of security.

BB84

BB84 is a quantum key distribution scheme which is provably secure if:

- the no-cloning theorem holds (information gain is only possible at the expense of disturbing the signal if the states we want to distinguish are not orthogonal)

-

the existence of an authenticated public classical channel.

- Alice generates a sequence of $n$ bits she wants to send. For every bit, she also randomly chooses a basis (either the computational basis or the Hadamard basis).

- Alice encodes the bits into qubits using the selected bases and transmits them.

- Alice sends the qubits to Bob.

- Bob also randomly chooses a basis to measure the qubits in for every bit. He measures the qubits.

- Bob announces that he has received the transmission. Alice announces the bases she used to encode the bits. Alice and Bob only keep the bits in the strings where they bases did match (probability $\frac{1}{2}$).

- From the remaining $k$ bits, Alice randomly chooses $\frac{k}{2}$ bits and discloses her choices over the public channel. Both Alice and Bob announce these bits publicly and run a check to see whether a certain amount of them agree. Then, error correction needs to be done on the resulting secret bits.

Shor’s Algorithm

Let $N$ be a positive integer and $b$ be a non-trivial square root of $1$ modulo $N$, i.e.

\[b^2 = 1\pmod{N}~\text{ and }~b \not= \pm1\pmod{N}\]Then $\gcd(b-1, N)$ is a non-trivial factor of $N$.

A sequence $x_1, x_2, x_3, \dots$ is periodic if there exists a number $r$ such that $x_{n+r} = x_n$ for all $n$. The smallest positive $r$ with this property is called a period of the sequence.

Let $a \in \Z^\times_N$ be arbitrary. Consider a sequence $x_1, x_2, x_3, \dots$ where

\[x_i = a^i \pmod{N}\]Let $r$ be the period of this sequence. If $r$ is even and $a^\frac{r}{2} \not= -1 \pmod{N}$, then $a^\frac{r}{2}$ is a non-trivial square root of $1$ modulo $N$. In particular, $\gcd(a^\frac{r}{2} - 1, N)$ is a non-trivial factor of $N$.

These are classical (not quantum), quite trivial number theory theorems. Shor’s algorithm quantum part is finding the period of a sequence $(a^i \pmod{N})^\infty_{i = 1}$.

Finding the period is done with a Fourier Transform, in this case Quantum Fourier Transform, which is exponentially faster than DFT.