Probability, Theory of Information

$\def\F{\mathscr{F}} \def\R{\mathbb{R}} \def\Im{\text{Im}} \def\Var{\text{Var}} \def\abs#1{|#1|} \def\bigabs#1{\left|#1\right|} \def\st{~|~} \def\set#1{\{#1\}} \def\condset#1#2{\{#1~|~#2\}}$

Probability. Discrete and continuous probability space. Random variables and their use. Mean value, variance. Stochastic processes, Markov chains. Theory of information (entropy, mutual information), coding theory (Huffman codes, noisy channel capacity). (IV111)

Other Sources

Random experiment is a model of physical or thought experiment, where we are uncertain about outcomes of the experiment. It is specified by the set of possible outcomes and probabilities that each particular outcome occurs.

Probability

Sample space is the non-empty set of possible outcomes of a random experiment, denoted by $S$. The outcomes of a random experiment are denoted by sample points.

Event of a random experiment with a sample space $S$ is any subset of $S$.

A probability function $P$ on a discrete sample space $S$ with a set of all events $\F = 2^S$ is a function $P: \F \to [0, 1]$ such that:

- $P(S) = 1$

for any countable sequence of pairwise disjoint events $A_1, A_2, \dots$

\[P\left(\bigcup_{i=1}^\infty A_i\right) = \sum_{i=1}^\infty{P(A_i)}\](countable additivity axiom)

Probability Spaces

Events $A_1, A_2, \dots, A_n$ are mutually exclusive iff

\[\forall i \not= j . A_i \cap A_j = \emptyset\]

Events $A_1, A_2, \dots, A_n$ are collectively exhaustive iff

\[A_1 \cup A_2 \cdots \cup A_n = S\]

Mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive subset of $S$ is called a partition of $S$.

A discrete probability space is a triple $(S, \F, P)$ where

- $S$ is a sample space,

- $\F = 2^S$ is a collection of all events,

- $P: \F \to [0, 1]$ is a probability function.

Let $S$ be a sample space. Then $\F \subseteq 2^S$ is a $\sigma$-field if

- $\emptyset \in \F$,

- if $A_1, A_2, \cdots \in \F$ then $\cup_{i=1}^\infty{A_i} \in \F$, and

- if $A \in \F$ then $\bar{A} \in \F$.

A probability space is a triple $(S, \F, P)$ where

- $S$ is a sample space,

- $\F \subseteq 2^S$ is a $\sigma$-field - a collection of sets representing the allowable events

- $P: \F \to [0, 1]$ is a probability function.

We cannot use $\F = 2^S$ because $\F$ has to be a measurable set.

Random Variables

We define random variables to develop methods for studying random experiments with outcomes that can be described numerically. Almost all probabilistic computation is done using random variables.

Discrete Random Variables

A discrete random variable $X$ on a sample space $S$ is a function $X: S \to \R$ that assigns a real number $X(s)$ to each sample point $s \in S$.

The image of a random variable $X$ is $\Im(X) = \condset{X(s)}{s \in S}$.

\[P([X = x]) = P(\condset{s \in S}{X(s) = x}) = \sum_{s:X(s)=x}{P(s)}\]For a random variable $X$ and $x \in \R$ we define the inverse image of $x$ to be the event

\[[X = x] = \condset{s \in S}{X(s) = x}\]i.e. the set of all sample points from $S$ to which $X$ assigns the value $x$.

Probability mass function (probability distribution) of a discrete RV $X$ is a function $p_X: \R \to [0, 1]$ given by

\[p_X(x) = P(X = x) = \sum_{s:X(s)=x}{P(s)}\]

The cumulative distribution function (distribution function) of a discrete RV $X$ is a function $F_X: \R \to [0, 1]$ given by

\[F_X(x) = P(X \leq x) = \sum_{t \leq x}{p_X(t)}\]

Continuous Random Variables

Given a probability space $(S, \F, P)$, a continuous random variable $X$ on a sample space $S$ is a function $X: S \to \R$ such that$

\[\condset{s}{X(s) \leq r} \in \F \text{ for each } r \in \R\]

The cumulative distribution function of a random variable $X$ is a function $F_X: \R \to [0, 1]$ given by

\[F_X(x) = P(X \leq x)\]

Probability density function of $X$ is the function $f_X: \R \to \R$, for which

\[F_X(x) = \int_{-\infty}^x f_X(t)dt\]holds.

Mean Value

Expectation (mean value) of a random variable $X$ is defined as

\[E(X) = \sum_{x \in \Im(X)}{x \cdot P(X = x)}\]provided the sum is absolutely convergent (is finite). In case the sum is convergent but not absolutely convergent, we say that no finite expectation exists.

For continuous variables:

\[E(X) = \int{x \cdot f_X(x) dx}\]Moments

The $k^{\text{th}}$ moment of a random variable $X$ is defined as $E(X^k)$.

The $k^{\text{th}}$ central moment of $X$ is

\[\mu_k = E([X - E(X)]^k)\]

Variance

The second central moment is known as the variance of $X$ and defined as

\[\Var(X) = \sigma_X^2 = E([X - E(X)])^2\]The square root of $\Var(X)$ is the standard deviation $\sigma_X$.

If variance is small, then $X$ takes values close to $E(X)$ with high probability. If the variance is large, then the distribution is more ‘diffused’.

Also, $\Var(X) = E(X^2) - [E(X)]^2$

Important Theorems

Markov inequality: Let $X$ be a nonnegative random variable with finite mean value $E(X)$. Then for all $t > 0$ it holds that

\[P(X \geq t) \leq \frac{E(X)}{t}\]Alternatively, for $k > 0$,

\[P(X \geq k \cdot E(X)) \leq \frac{1}{k}\]

Chebyshev inequality: Is Markov inequality applied to the variable $[X - E(X)]^2$. Let $X$ be a random variable with finite variance. Then

\[P[\abs{X - E(X)} \geq t] \leq \frac{\Var(X)}{t^2}, t > 0\]

Weak Law of Large Numbers: If $X_1, X_2, \dots$ is a sequence of i.i.d. random variables with expectation $\mu = E(X_k)$, then for every $\varepsilon > 0$

\[\lim_{n \to \infty}{P\left(\bigabs{\frac{X_1 + \cdots + X_n}{n} - \mu} > \varepsilon\right)} = 0\]

The Weak Law of Large Numbers states that the probability the average of $X_i$ differs from the expectation by any positive value goes to 0 with the increasing number of samples.

Strong Law of Large Numbers: If $X_1, X_2, \dots$ is a sequence of i.i.d. random variables with expectation $\mu = E(X_k)$, then

\[P\left(\lim_{n \to \infty}{\frac{X_1 + \cdots + X_n}{n} = \mu}\right) = 1\]

The Strong Law of Large Numbers states that for every infinite sequence the average of it has zero probability to differ from the expectation.

Stochastic Processes

A stochastic process is a collection of random variables $X = \condset{X_t}{t \in T}$. The index $t$ often represents time; $X_t$ is called the state of $X$ at time $t$.

- The time domain $T$ can be either countable (discrete-time process), or uncountable (continuous-time process).

- The state space of $X_t$ can be finite (finite-state process), countable (discrete-state process), or uncountable (continuous-state process).

Markov Chains

A discrete-time stochastic process $\set{X_0, X_1, X_2, \dots}$ is a time-homogeneous Markov chain if

- $P(X_t = x_t \st X_{t - 1} = x_{t - 1}, X_{t - 2} = x_{t - 2}, \cdots, X_0 = x_0) = P(X_t = x_t \st X_{t - 1} = x_{t - 1})$ (Markov/memoryless property)

- $P(X_t = x \st X_{t - 1} = y) = P(X_1 = x \st X_0 = y)$ for all $n$ (time-homogeneous property)

A discrete-time Markov chain is a tuple $(S, P, \pi_0)$ where

- $S$ is the set of states,

- $P: S \times S \to [0, 1]$ with $\sum_{s’ \in S}{P(s, s’) = 1}$ is the transition matrix, and

- $\pi_0 \in [0, 1]^{\abs{S}}$ with $\sum_{s \in S}{\pi_0(s) = 1}$ is the initial distribution.

The $m$-step transition matrix $P^{(m)} = P^m$ gives us the $m$-step reachability for all pairs of states in $S$.

The hitting time of a set of states $A \subseteq S$ is a random variable $H^A: \Omega \to \set{0, 1, 2, \cdots} \cup \set{\infty}$ given by

\[H^A(\omega) = \inf\condset{n \geq 0}{X_n(\omega) \in A}\]

We write $i \Rightarrow^* j$ as an abbreviation for $H^{\set{j}} < \infty$ given $X_0 = i$ (starting from state $i$, we eventually visit $j$).

We write $i \Rightarrow^+ j$ as an abbreviation for $0 < H^{\set{j}} < \infty$ given $X_0 = i$ (starting from state $i$, we eventually visit $j$ in a positive number of steps).

Starting from a state $s$, the probability of hitting $A \subseteq S$ is

\[h_s^A = P(H^A < \infty \st X_0 = s)\]and the mean time taken to reach a set of states $A$ is

\[\begin{align*} k_s^A &= E(H^A \st X_0 = s)\\ &= \sum_{n < \infty}{n \cdot P(H^A = n \st X_0 = s)} + \infty \cdot P(H^A = \infty \st X_0 = s) \end{align*}\]where $0 \cdot \infty = 0$.

State Classification

A state $i$ of a Markov chain is said to be absorbing iff it cannot be left once it is entered ($p_{i,i} = 1$).

A state $i$ of a Markov chain is said to be recurrent iff, starting from state $i$, the process eventually returns to state $i$ with probability 1, i.e.

\[P(i \Rightarrow^+ i) = 1\]

A state of a Markov chain is said to be transient (non-recurrent) iff there is a positive probability that the process will not return to this state, i. e.

\[P(i \Rightarrow^+ i) < 1\]

Every transient state is visited finitely many times almost surely (with probability 1).

In a finite-state Markov chain, each recurrent state is almost surely either not visited or visited infinitely many times.

Markov Chain Analysis

Transient analysis:

- distribution after $k$ steps

- the $k$-th power of the transition matrix

- reaching/hitting probability

- (mean) hitting time

Long-run analysis:

- probability of infinite hitting

- mean inter-visit time

- long-run limit distribution

- stationary (invariant) distribution

Continuous-Time Markov Chains

Exponential distribution is (the only continuous) memoryless distribution:

For an exponentially distributed random variable $X$ and every $t, t_0 \geq 0$, it holds that

\[P(X > t_0 + t \st X > t_0) = P(X > t)\]

A Continuous-Time Markov Chain is an event-driven system with exponentially distributed events.

Queues

Queues are an example of CTMC.

Kendall notation: A/S/n/B/K, where

- A: inter-arrival time distribution (G - general, M, exponential, D - deterministic)

- S: service time distribution (G - general, M, exponential, D - deterministic)

- n: number of servers ($1, 2, \dots, \infty$)

- B: buffer size ($1, 2, \dots, \infty$), implicit value $\infty$

- K: population size ($1, 2, \dots, \infty$), implicit value $\infty$

Discretization: for long-run average (steady-state) propertiess

Theory of Information

Entropy

Let $X$ be a random variable with a probability distribution $p(x) = P(X = x)$. Then the (Shannon) entropy of the random variable $X$ is defined as

\[H(X) = -\sum_{x \in \Im(X)} p(x) \log p(x)\]

Let $X$ and $Y$ be random variables and $y \in \Im(Y)$. The conditional entropy of $X$ given $Y = y$ is

\[H(X \st Y = y) = - \sum_{x \in \Im(X)} P(X = x \st Y = y) \log P(X = x \st Y = y)\]

Let $X$ and $Y$ be random variables with a joint probability distribution $p(x, y) = P(X = x, Y = y)$. Let us denote $p(x \st y) = P(X = x \st Y = y)$. The conditional entropy of $X$ given $Y$ is

\[\begin{align*}H(X \st Y) &= \sum_{y \in \Im(Y)} p(y) H(X \st Y = y) \\ &= -\sum_{y \in \Im(Y)} p(y) \sum_{x \in \Im(X)} p(x \st y) \log p(x \st y) \\ &= -\sum_{x \in \Im(X)} \sum_{y \in \Im(Y)} p(x, y) \log p(x \st y) \\ &= -E_p [\log p(X \st Y)] \\ \end{align*}\]

Chain Rule of Conditional Entropy

Let $X$ and $Y$ be random variables. Then, $H(X, Y) = H(Y) + H(X \st Y)$.

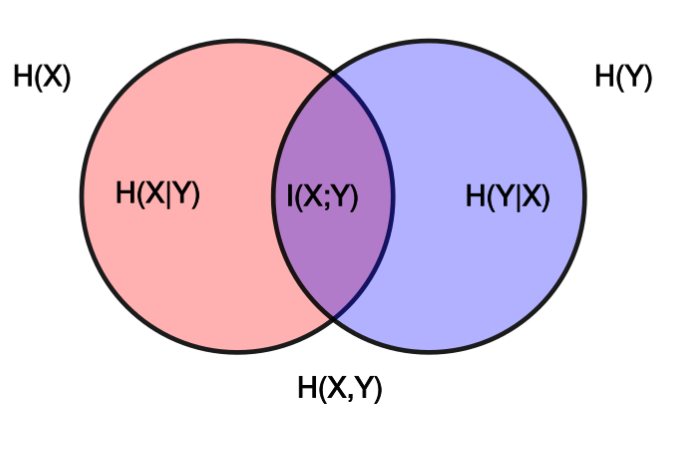

Mutual Information

The cross-entropy of the distribution $q$ relative to a distribution $p$ on a common set of sample points $\Im(X)$ is defined as

\[H(p \Vert q) = -\sum_{x \in \Im(X)}{p(x) \log{q(x)}} = -E_p[\log{q(X)}]\]

The relative entropy measures the inefficiency of assuming that a given distribution is $q$ when the true distribution is $p$.

The relative entropy (Kullback-Leibler divergence) between two probability distributions $p(x)$ and $q(x)$ on a common set of sample points $\Im(X)$ is defined as

\[D(p \Vert q) = -\sum_{x \in \Im(X)}{p(x) \log{\frac{p(x)}{q(x)}}} = -E_p\left[\log{\frac{p(X)}{q(X)}}\right]\]If $p$ and $q$ images differ, we use $0 \log \frac{0}{q} = 0$ and $p \log \frac{p}{0} = \infty$.

Note that $D(p \Vert q) = H(p \Vert q) - H(p)$.

Let $X$ and $Y$ be random variables with a joint distribution $p$. The mutual information $I(X; Y)$ is the relative entropy between the joint distribution and the product of marginal distributions $p_X$ and $p_Y$

\[I(X; Y) = D(p \Vert (p_X \cdot p_Y)) = E_p \left[ \log\frac{p(X, Y)}{p_X(X)p_Y(Y)} \right]\]

Also, $I(X; Y) = H(X) - H(X \st Y)$ and from the symmetry, $I(X; Y) = H(Y) - H(Y \st X)$.

As $H(X, Y) = H(X) + H(Y \st X)$, we get

\[\begin{align*} I(X; Y) &= - H(X, Y) + H(X) + H(Y \st X) + H(Y) - H(Y \st X) \\ &= H(X) + H(Y) - H(X, Y) \end{align*}\]

Coding Theory

We model the source of information as a random variable $X$ with all possible messages equal to $\Im(X)$. The source emits the message $x$ with probability $P(X = x)$. A sequence of messages is created by a sequence of independent trials described by $X$ and thus by a random process $X_1, X_2, \dots$ where $X_i$ are i.i.d. - a memoryless source.

A code $C$ for a random variable (memoryless source) $X$ is a mapping $C: \Im(X) \to D^{*}$, where $D^*$ is the set of all finite-length strings over the alphabet $D$. With $\abs{D} = d$, we say the code is $d$-ary, $C(x)$ is the codeword assigned to $x$ and $l_C(x)$ denotes the length of $C(x)$.

The expected length $L_C(X)$ of a code $C$ for a random variable $X$ is given by

\[L_C(X) = \sum_{x \in \Im(X)}{P(X = x) l_C(x) = E[l_C(X)]}\]

We will assume (WLOG) that the alphabet is $D = \set{0, 1, \dots, d - 1}$.

A code $C$ is said to be non-singular if it maps every element in the range of $X$ to different string in $D^*$, i.e.

\[\forall x, y \in \Im(X) . x \not= y \Rightarrow C(x) \not= C(y)\]

Non-singularity allows decoding of any single keyword, but in practice we need to be able to decode a sequence of keywords.

Let $\Im(X)^+$ denote the set of all nonempty strings over the alphabet $\Im(X)$.

An extension $C^{*}$ of a code $C$ is the mapping from $\Im(X)^+$ to $D^{*}$ defined by

\[C^{*}(x_1 x_2 \dots x_n) = C(x_1)C(x_2)\dots C(x_n)\]A code is uniquely decodable iff its extension is non-singular.

A uniquely decodable code has only one possible source string for every encoded string.

A code is called a prefix code if no codeword is a prefix of any other keyword.

All prefix codes are trivially uniquely decodable, moreover a codeword can be decoded as soon we read its last symbol.

Kraft Inequality

For any prefix code over an alphabet of size $d$, the codeword lengths (including multiplicities) $l_1, l_2, \dots, l_m$ satisfy

\[\sum_{i = 1}^m{d^{-l_i}} \leq 1\]Conversely, given a sequence of codeword lengths that satisfy this inequality. there exists a prefix code with these codeword lengths.

Proof

Consider a $d$-ary tree in which every inner node has $d$ descendants. Each edge represents a choice of a code alphabet symbol at a particular position. Each codeword is represented by a node (does not hold the other way) and the path from the root to a particular node (codeword) specifies the codeword symbol. The prefix condition implies that no codeword is an ancestor of another codeword on the three.

Let $l_{\max} = \max\set{l_1, l_2, \dots, l_m}$. Consider all nodes of the tree at the level $l_{\max}$. A codeword at level $l_i$ has $d^{l_{\max} - l_i}$ descendants at level $l_{\max}$. Sets of descendants of different codewords must be disjoint and the total number of nodes in all these sets must be at most $d^{l_{\max}}$. Summing over all codewords we have

\[\sum_{i = 1}^m{d^{l_{\max} - l_i}} \leq d^{l_{\max}}\]and hence

\[\sum_{i = 1}^m{d^{-l_i}} \leq 1.\]Conversely, given any set of codeword lengths $l_1, l_2, \dots, l_m$ satisfying the Kraft inequality we can always construct a tree described above. We may WLOG assume that $l_1 \leq l_2 \leq \cdots \leq l_m$.

Label the first note of depth $l_1$ as the codeword $1$ and remove its descendants from the tree. Then mark first remaining node of depth $l_2$ as the codeword $2$. Continue for all the remaining nodes. We need to show there is enough nodes for this algorithm to work.

Assume that for some $i \leq m$ there is no free node of level $l_i$ when we want to add a new codeword of length $l_i$. This, however, means that all nodes at level $l_i$ are either codewords or descendants of a codeword, giving

\[\sum_{j = 1}^{i - 1}{d^{l_i - l_j}} = d^{l_i}\]which is equivalent to $\sum_{j=1}^{i - 1}{d^{-l_j}} = 1$. But we still have the codeword $i$ to add, meaning $\sum_{j = 1}^i {d^{-l_j}} > 1$, violating the initial assumption.

McMillan Inequality

For any uniquely decodable code over an alphabet of size $d$, the codeword lengths (including multiplicities) $l_1, l_2, \dots, l_m$ satisfy

\[\sum_{i = 1}^m{d^{-l_i}} \leq 1\]Conversely, given a sequence of codeword lengths that satisfy this inequality. there exists a uniquely decodable code with these codeword lengths.

Optimal Codes

The task is to find the prefix code with the minimum expected length.

The expected length of any prefix $d$-ary code $C$ for a random variable $X$ is greater than or equal to the entropy $H_d(X)$ ($d$ is the base of the logarithm), i.e.

\[L_C(X) \geq H_d(X)\]with equality iff for all $x_i$: $P(X = x_i) = p_i = d^{-l_i}$ for some integer $l_i$ (a $d$-adic distribution).

Naive Shannon-Fano Coding

Choose word lengths such that

\[l_i = \left\lceil\log_d\left(\frac{1}{p_i}\right)\right\rceil\]

Shannon-Fano Coding is not optimal!

The choice of codeword lengths satisfies

\[\log_d \frac{1}{p_i} \leq l_i < \log_d{\frac{1}{p_i}} + 1\]Taking expectation over $p_i$ on both sides, we get

\[H_d(X) \leq L_C(X) < H_d(X) + 1\]Huffman Codes

The $d$-ary Huffman code for source described by the random variable $X$ with probability distribution $p_1, p_2, \dots, p_m$ is constructed by the following steps:

- Add redundant input symbols with probability $0$ to the distribution so that the distribution has $1 + k(d - 1)$ symbols for some $k$

- Take a list of symbols and their probabilities.

- Select $d$ symbols with the lowest probabilities (if multiple symbols have the same probability, select $d$ arbitrarily).

- Create a $d$-ary tree out of these $d$ symbols, labeling branches with $\set{0, \dots, d-1}$ consecutively.

- Add the probabilities of the $d$ symbols to get the probability of the new subtree.

- Remove the symbols from the list and add the subtree to the list.

- Go back through the list and take the $d$ symbols/subtrees with the smallest probabilities and combine those into a new subtree. Remove the original symbols/subtrees from the list, and add the new subtree to the list.

- Repeat until all of the elements are combined.

Huffman codes are optimal, i.e. the codes obtained by the Huffman algorithm assigns codewords of same lengths as optimal ones.

Channels

A discrete channel is a system $(X, p(y \st x), Y)$ consisting of an input alphabet $X$, output alphabet $y$, and a probability transition matrix $p(y \st x)$ specifying the probability we observe $y \in Y$ when $x \in X$ was sent.

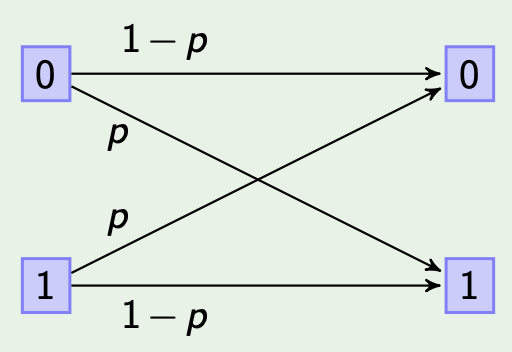

Example: Binary symmetric channel preserves its input with probability $1 - p$ and outputs the negation of the input with probability $p$.

Let $x^k = x_1, x_2, \dots x_k, X^k = X_1, X_2, \dots, X_k$.

A channel is said to be without feedback if the output distribution does not depend on past output symbols, i.e. $p(y_k \st x^k, y^{k-1}) = p(y_k \st x^k)$

A channel is said to be memoryless if the output distribution depends only on the current input and is conditionally independent of previous channel inputs and outputs, i.e. $p(y_k \st x^k, y^{k-1}) = p(y_k \st x_k)$.

The $n$-th extension of the discrete memoryless channel is the channel $(X^n, p(y^n \st x^n), Y^n)$, where

\[p(y_k \st x^k, y^{k-1}) = p(y_k \st x_k)\]for $k = 1, 2, \dots, n$.

An $(M, n)$ code for the channel $(X, p(y \st x), Y)$ consists of the following:

- A set of input messages $\set{1, 2, \dots, M}$.

- An encoding function $f: \set{1, 2, \dots, M} \to X^n$ , yielding codewords $f(1), f(2), \dots, f(M)$.

- A decoding function $g: Y^n \to \set{1, 2, \dots, M}$, which is a deterministic rule assigning a guess to each possible receiver vector.

The rate $R$ of an $(M, n)$ code is

\[R = \frac{\log_2 M}{n}\]bits per transmission.

Channel Capacity

The channel capacity of a discrete memoryless channel is

\[C = \max_{p_X}{I(X; Y)}\]where $X$ is the input random variable, $Y$ describes the output distribution and the maximum is taken over all possible input distributions $p_X$.

Probability of an error for the code $(M, n)$ and the channel $(X, p(y \st x), Y)$ provided the $i$-th index was sent is

\[\lambda_i = P(g(Y^n) \not= i \st X^n = f(i))\]The maximal probability of an error for an $(M, n)$ code is

\[\lambda_{\max} = \max_{i \in \set{1, 2, \dots, M}}\lambda_i\]

Channel Coding Theorem

Let $C$ be a capacity of a communication channel and $R$ be a code rate.

- If $R < C$, then for any $\varepsilon > 0$ there exists a code with rate $R$ (and large enough block length $n$) whose error probability $\lambda_{\max}$ is less than $\varepsilon$.

- If $R > C$, the error probability $\lambda_{\max}$ of any code with rate $R$ is bounded away from zero.